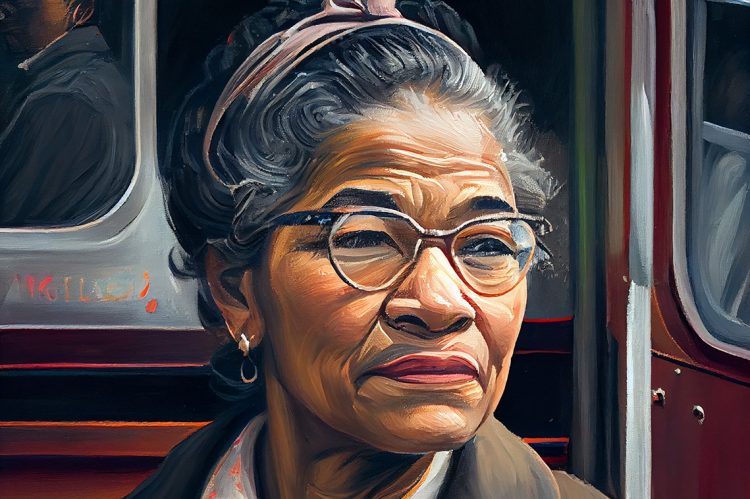

As part of Black History Month, we’ve been celebrating Black leaders on the blog and for today’s post, I’d like to talk about leadership lessons from Rosa Parks.

Parks is credited with helping to initiate the civil rights movement in the U.S. after she famously refused to give up her seat to a white man while riding a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. At the time, African Americans were required by city ordinance to sit in the back half of all city buses and yield their seats to white bus riders should the front half of the bus become full.

According to History.com, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks–a seamstress from Tuskegee, Alabama and a respected member of the African American community in Montgomery–was sitting in the front row of what was called the “colored section” of the Cleveland Avenue bus. She had just finished a long day of work at the Montgomery Fair department store. When the “white seats” filled up, the bus driver asked four Black riders to give up their seats, as per the existing city ordinance. Three of those riders vacated their seats but the fourth rider–Rosa Parks–wouldn’t budge.

In her official autobiography, Parks recalls that pivotal decision. She wrote: “People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

By the time she was sent to jail, everyone in the Montgomery community had heard about Parks’ arrest, including the former head of the Montgomery National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, E.D. Nixon. He’d been waiting for the perfect case that could challenge the segregated bus system in Montgomery…and believed he’d just found it in the unstoppable Rosa Parks.

As Stanford University’s King Institute describes, a group quickly assembled to bail Parks out of jail, including: Park’s close friend Virgina Durr; Virginia’s husband, Clifford Durr; and E.D. Nixon. Virginia Durr played a pivotal role in Parks’ civil rights advocacy; in 1955, Durr organized for Parks to receive a scholarship to attend a two-week workshop at the Highlander Folk School. The workshop focused on the implementation of school desegregation and cultivating local leaders for social change. What Parks learned at that workshop is believed to have (at least in part) inspired her actions on the Cleveland Avenue bus. Durr’s husband, Clifford Durr, was a lawyer who long championed diversity and equal rights.

Back at home, Parks spoke with Nixon about her case and its potential to ignite real change in the Montgomery community and around the country. The following day, when Parks’ trial was set to take place, there’d also be a citywide bus boycott and by midnight, 35,000 flyers were sent out with details about the upcoming event.

On December 5, 1955, History.com describes that about 40,000 Black bus drivers (most of the drivers in the city) participated in what would become known as the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Later in the afternoon, Black organizers also formed the Montgomery Improvement Association and elected a 26-year-old pastor from Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church as the president of the group. His name? Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott continued for 13 months–exactly 381 days–until December 20, 1956 when the Montgomery buses became officially integrated. Several months later, on June 5, 1956 a federal district court in Montgomery ruled that bus segregation was in violation of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In November 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision.

So, what’s the message? One of my father’s favorite quotes was that the tallest oak tree in the forest was just a little nut that held its ground. Stand tall. Fight for what you believe in. Have courage. Be brave. Parks once said: “To bring about change, you must not be afraid to take the first step. We will fail when we fail to try.”

This article is adapted from Blefari’s weekly, company-wide “Thoughts on Leadership” column from HomeServices of America.