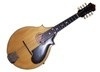

RISMEDIA, February 13, 2009-(MCT)-For years, an old mandolin that was passed down as a family heirloom held a secret from two sisters.

RISMEDIA, February 13, 2009-(MCT)-For years, an old mandolin that was passed down as a family heirloom held a secret from two sisters.

Jody Kennedy had used the aged, wooden instrument as a sentimental fireplace decoration in her Olathe, Kan., home until sister Phyllis Shanline of Manhattan, Kan., wanted to learn to play it, so a family member took it to a Lawrence, Kan., shop for repairs. The next stop: a UMB bank vault in downtown Kansas City, Mo.

Its secret? The 1924 Gibson F5 Master Model mandolin their father once played is worth $165,000, and some similar instruments have sold for more than $200,000 in recent years.

“I was shocked,” Shanline said. “I sat down right away, and I think I’ve had high blood pressure ever since.” Their mandolin, a small instrument with four pairs of strings that are plucked, for them was simply an heirloom that brought back memories of a father who once played it but who died in 1961. Its strings are rusty, and a few are missing. Dust and white paint specks mar the varnish, as do a few wood cracks.

Kennedy, 73, in recent years used it to decorate a fireplace ledge. The curled scroll atop the body, f-shaped holes in the top and the elongated points on the body- along with fern-like pearl inlay on the headstock- gave it a classical look.

“It looked so pretty sitting there,” she said.

All this time they had paid little attention to the paper labels glued inside the mandolin’s sound chamber, clues that gave away its elite pedigree as the Stradivarius of mandolins.

One label included the signature of mandolin designer Lloyd A. Loar and the date March 24, 1924, which signified that he had personally inspected the instrument and likely played it to ensure its perfection.

The sisters are now marveling at the revered lineage of their father’s mandolin and how his love of music is providing for them now.

“It does kind of boggle the mind,” Kennedy said. “He’s still giving to us.”

Family Band

Back in the 1930s, or earlier, Victor and Lena Semisch of rural Butler County, Kan., acquired the Gibson F5 and a Gibson guitar for Lena. Victor taught at a country school and later operated a general store and gas station near Augusta, Kan.

Shanline, 80, formerly of Shawnee, Kan., remembers her father teaching her how to sing harmonies as he she rode with him to make gas deliveries to farmers. She has vague memories of the mandolin and of him playing the song “Red Wing” on it.

Kennedy remembers seeing the mandolin once when she was young and her father playing it a bit.

Their parents played country music at local gatherings, but the sisters paid little attention.

“I thought, ‘Why on earth can’t they play something up to date?'” Shanline said.

Their parents didn’t play much after World War II, Kennedy said. After her husband died, Lena Semisch held on to the instruments.

Both the mandolin and the guitar survived a couple of house fires. Kennedy acquired the mandolin in 2001 after her mother died. Then Shanline decided she’d like to learn to play her father’s mandolin.

A family member took it recently to Dave Wendler of Lawrence, Kan., who repairs and builds instruments. He was amazed to see a black, rectangular case with the Loar inside.

“I’ve been involved in instrument repair since 1975, and this is the first one I’ve had in my hands,” Wendler said. “This is a once-in-a-lifetime thing.”

An American Classic

Loar-signed Gibson F5 mandolins are obscure to mainstream America, but they’re worshipped for their tone, craftsmanship and rarity by musicians and instrument collectors.

Only 228 Loar-signed Gibson F5 mandolins are documented, of an estimated 326 that were made under his supervision from 1922 through 1924, according to expert Darryl G. Wolfe of South Carolina, who records each Loar in a publication called The F5 Journal.

Mandolins were the rage in the early 1900s. But the older, round-back Italian designs and the newer and flatter American models didn’t have the power and tonal range of the violin.

Then Loar, a virtuoso mandolinist interested in physics, refined the F5 style for the Gibson Mandolin-Guitar Co. so the instrument was easier to play and clearly projected a louder, more complex tone.

Unfortunately, the jazz age had begun and popular music moved away from mandolins. Loar left Gibson late in 1924, and he died in 1943.

Most F5 mandolins signed by him gathered dust in closets and attics, until Grand Ole Opry star and mandolin player Bill Monroe in the 1950s and 1960s began drawing young musicians to his bluegrass music. A new acoustic music generation of jazz and bluegrass artists arose in his footsteps and, like Monroe, they wanted to play a Loar F5.

“There is nothing like its unique tone and nothing to compare with its intense rarity and the number of players who yearn to own, touch, play one,” said Stan Jay, owner of the world-famous Mandolin Brothers music store in New York. “It is the Holy Grail, in a unique Cremona sunburst varnished finish that would have made Antonio Stradivari salivate.”

Passing It On

Today there’s a whole industry based on making copies of Loar’s F5. But not many replicas measure up to the original, or if they do, they still don’t have the master designer’s signature.

So Loar-signed instrument prices have soared through the years, with both players and investors buying. Shanline and Kennedy have decided to sell theirs, with Wendler serving as broker. They figure their father would want them to use the money to help their families, and they hope the instrument goes to someone who loves music and poetry like he did.

Setting a price on something they once viewed simply as a family curio was tricky. They settled on $165,000, due to needed repairs and an economy in recession.

“I had no idea it was worth that,” Kennedy said. “I wouldn’t have set it out by the fireplace if I had.”

© 2009, The Kansas City Star.

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.