Though it may seem hyperbolic or cliche, the stakes have never been higher in what has shaped up to become some of the most anticipated—and dreaded—legal battles the industry has faced.

Industry pundits have spent the better part of four years weighing in on the possible implications of the Moehrl and Burnett/Sitzer lawsuits, and the consensus has been that each case carries potentially disastrous consequences on different levels.

“At a high level, this is one piece of what I consider to be an existential moment for the industry in terms of how it goes about its work,” says Cofano. “That doesn’t mean it’s a bad moment. It means it’s going to be a moment that, if things happen as I and others think are going to take place, it will dramatically affect all the various interconnected relationships in the business, starting with the relationship between consumers and agents.”

It’s easy to focus on the lawsuits as if they were in a vacuum. However, Cofano points out that those legal battles are also combined with the federal government’s—specifically the DOJ’s—intent to change the payment structure of the industry.

And again, the DOJ has made it clear that a tweak to the buyer agent commission offer is potentially not enough to stem allegedly illegal practices in the industry, writing that “(e)vidence from other multiple listing services suggests that merely tweaking a buyer-broker commission rule to allow zero-percent commissions does little to ‘unfetter a market from anti-competitive conduct’.’”

Cofano foresees this push creating bigger changes in the long run.

“That, combined with the lawsuits and the potential for negative results toward the industry from those lawsuits and then concurrent government policy changes and intrusion, I think, will have major impacts on how the industry does business,” Cofano says.

Aside from the potential for a pair of multi-billion-dollar payouts that could instantaneously crumble NAR and several prominent franchisors, each case could fundamentally dismantle the current cooperative commission structure that has been a fixture in residential real estate.

While there is plenty of speculation regarding what losses in court might mean for the industry, pundits suggest that the implications can vary depending on how each case plays out.

Untethered Commissions

Robert Hahn, managing partner of 7DS Associates, points out a range of outcomes that hinge to a large degree on the Judge’s discretion. That spectrum looks at whether the judges allow NAR to make a seemingly simple change to the policy language.

“One option is that (a buyer commission offer) just becomes optional,” he explains. “However, the other extreme is where it’s just simply banned, and you’re not allowed to share compensation at all,” Hahn adds.

The latter would set the stage for a separation of agent commissions—also known as a “decoupling” of commissions.

Plaintiffs and their supporters have also argued that decoupling agent commissions—buyers and agents pay their respective agents—could “spur price competition” and reduce billions of dollars in commissions paid by consumers annually.

However, real estate pundits argue the contrary.

Ken H. Johnson, an economist at Florida Atlantic University’s (FAU) College of Business, tells RISMedia that doing away with a cooperative commission structure would ultimately place an additional financial burden on buyers who want representation in a transaction.

“That’s just more money the buyer has to come up with at closing, and it actually puts them in a bit of a rough position to where now because I’m going to have somebody represent me, I actually have to come up with more money at closing,” he says.

Katie Johnson echoed similar sentiments.

“Having to come up with that money at closing would eliminate many buyers from the market entirely, which is bad for buyers and sellers alike,” she says. “Any amount that they’d have to put down in addition to the down payment will mean that they can spend less on a home.”

She points out that some proponents of uncoupling commissions have suggested rolling the buyer’s agent fees into a mortgage.

“The price of mortgage payments would increase monthly,” she says. “The overall loan price would increase tremendously more than they spend today.”

NAR came out explicitly against rolling buyer commission into mortgages in the days leading up to the Burnett trial, arguing that such a change would be complex, uncertain and potentially an overall negative for consumers. At the same time, NAR is “exploring options” for the eventuality of buyers having to pay their own agents.

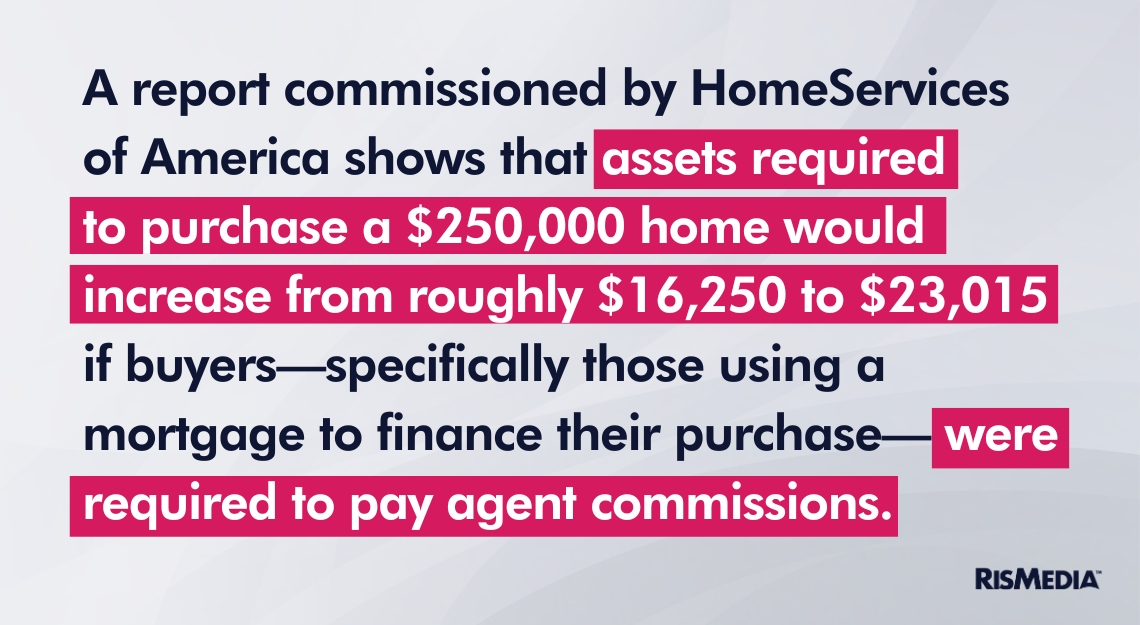

Last year, HomeServices of America commissioned a study examining the potential implications of indulging a proposed decoupling of agent compensation. The report claims that a buyer-paid commission structure would result in reduced homeownership opportunities for cash-constrained families and lower net proceeds for many sellers.

“Among other things, proponents of this approach have failed to consider an important benefit of the current compensation structure, namely, that it minimizes the amount of upfront cash required to buy a home,” the report read.

With the help of an economic model depicting the financial impact of changing the current compensation structure, HomeServices of America’s report shows that first-time, low-income, middle-income and racial-minority buyers would be the most affected by a shift in the commission structure.

“If the buyer ends up paying a 3% fee to their real estate agent, the amount of cash required at closing would rise by 42%,” the report reads. “While the percent change in cash requirements declines with increases in the buyer’s ability to negotiate a better rate, even a 1.5% commission—which has been used to illustrate the potential advantages of the so-called English model—would increase the cash required at closing by 19%.”

For example, the report shows that assets required to purchase a $250,000 home would increase from roughly $16,250 to $23,015 if buyers—specifically those using a mortgage to finance their purchase—were required to pay agent commissions.

At a time when buyers en masse are struggling to save for a down payment, Johnson claims the added fee would strain purchasing power in the buyer pool.

It is not clear that these sorts of studies will be able to turn the tide of consumer sentiment—or convince a judge or jury. In the Burnett trial, evidence showing that real estate rules are pro-competitive were disallowed by the judge based on a specific interpretation of the antitrust issues at play, and lawyers for the plaintiffs repeatedly questioned the credibility of data and studies commissioned by the defendants.

And the same judge who oversaw the Burnett trial will be overseeing an identical national class-action suit, filed by the same lawyers who represented the plaintiffs in the Burnett case.

But advocates for so-called “cooperative commission” continue to publicly warn against tearing the system down.

“The challenge, and what the industry freaked out about, is most people who are buying a home are in the worst financial position from a cash standpoint at that point in their lives, so they’re simply not going to be able to pay an agent,” Hahn says. If you can’t share commissions at all, then the number of buyers will (decline) because they have to pay somebody or go unrepresented.

de Souza took that concept further, suggesting that more buyers may choose to go unrepresented during transactions rather than pay an extra fee.

“It’d be like going to court but not being able to afford a lawyer, and you go without a lawyer,” he says.

While that would undoubtedly create issues for buyers in the market, an increase in buyers without an agent poses its own threat to the industry in the form of fading buyer agency.

A key dispute in the Burnett trial was over the demise of buyer sub-agency in the 1990s, which NAR claimed was a result of free-market forces and an indisputably pro-competitive and pro-consumer change. Buyers having their own representative is obviously a positive development, NAR lawyers argued, and ending the system that has allowed the vast majority of buyers to work with an agent would be regressive.

Whether this reasoning resonates with the public more than it did with a Kansas City jury is an open question. In the wake of the trial, NAR promised to continue championing “cooperative compensation” and the value of buyer agents.

Another potential consequence of adding more financial burden on buyers is a decline in viable buyers in the market, which also affects sellers.

However, a new structure could resolve that issue in the long term.

An example in HomeServices of America’s commissioned report offers a glimpse into that scenario, depicting a structure where sellers tweak their listing prices to account for the fee they would no longer have to pay to a buyer broker in the transaction.

For example, a home selling for $250,000 is lowered to $242,000, and where the seller and buyer pay $7,500 to their respective agent—assuming the commission is 3% per agent—the seller would still net the same amount at closing as they would under the current structure.

The buyer, theoretically, would also spend around the same amount under the proposed structure as they would under the current commission structure.

Johnson also suggests that upending the buyer-broker commission policy and forcing buyers to pay their agents could lead to a bifurcation between brokers on both sides of the deal table.

Multi-Level, Financial Turmoil

One of the most significant and harrowing stakes is the possible financial ruin for all defendants. Above all else, Burnett/Sitzer and Moehrl plaintiffs seek damages for the classes established in their respective suits.

If the court rules in favor of the plaintiffs in the Moehrl case, millions of home sellers in 20 MLS markets could ask to be reimbursed for an estimated $13.7 billion in damages. If the court awards treble damages—triple the actual damages—that figure could exceed $40 billion.

While the damages in Burnett are considerably lower than what is estimated in Moehrl (with the class covering a smaller geographic area), the $1.8 billion in damages assessed by the jury still rocked the industry. The judge still has the power to reduce that number, and NAR has said they are asking for that, as the organization also appeals the verdict.

Nevertheless, neither NAR nor its fellow defendants can cover the full tab of just that judgement, let alone two, which raises plenty of questions about how damages could be doled out.

“The absolute worst-case scenario would be some sort of catastrophic payout that would create bankruptcy that would reverberate across the industry,” says Edgerton.

Admittedly, Edgerton doesn’t expect either lawsuit to end with a financial death blow to NAR or the major franchisors named in the case.

“No lawyers are going to want to bankrupt an entire industry ultimately, nor would the judicial system,” Edgerton says, adding that when the dust settles, the defendants may find themselves in a survivable scenario of “extended yet painful payments that go on for several years.”

A more favorable outcome—depending on whom you ask—in the face of a loss could be settling with the plaintiffs on the monetary damages.

“You have many people looking at these cases from a state-law standpoint,” Cofano says. “These cases are brought in the federal courts under federal law, but similar state and antitrust laws apply to the same type of actions being claimed in federal court.”

Plaintiffs and defendants in the Burnett case sparred over the complex intersection of federal and state-level antitrust law, with the defendants attempting to cite Missouri law as potentially supporting their case.

“Even if the defendants wanted to settle the federal cases, that would not stop somebody from bringing the exact same case in state court,” Cofano continues. “There would be little incentive for the plaintiffs to settle these cases without knowing that they were truly settling the matter as opposed to pushing these litigations to class actions in the state court.”

According to Hahn, the possibility of ending up in the rigamarole of bankruptcy court may incentivize the plaintiffs to work with NAR and the company to reach an agreement on payouts.

“All these lawyers want to get paid, and they’re seeing enormous amounts of money on the other side,” Hahn says.

The most recently filed lawsuit, Gibson v. NAR et al, is attempting to take the Burnett case nationally. Naming NAR along with seven other large corporate brokerages (Compass, eXp, Redfin, Weichert, United Real Estate, Howard Hanna and Douglas Elliman). It is hard to make any comprehensive assessment regarding that suit in these very early stages (it was filed within hours of the Burnett verdict) but a potential class could include hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of recent homesellers.

The plaintiffs in Burnett calculated roughly $6,000 in damages per seller—though a national class could very well have a different damage assessment, based off of how much a jury decided they overpaid for buyer commission.

With these numbers likely adding up to tens of billions even if the damages are eventually reduced, settlements are seeming more and more likely. RE/MAX and Anywhere paid a combined $138 million to settle both the Burnett and Moehrl cases, which the other defendants called “pennies on the dollar” based on the billions in damages at stake.

That reference, made in a court filing before the Burnett trial, was meant to paint the plaintiffs’ claims as flimsy, based on how much the plaintiffs were demanding. After the verdict, that settlement is being viewed in a totally different light (though a successful appeal could again alter the calculus).

RE/MAX and Anywhere are also not fully off the hook, either. A concurrent class action lawsuit, formerly know as Leeder v. NAR et al, alleges that buyers were harmed by the essentially the same rules that Burnett and Moerhrl plaintiffs claimed were harmful to sellers. The settlement agreement that those two companies reached does not cover this suit, which was dismissed but refiled.

Another settlement came in the Nosalek v. MLS PIN case, which saw plaintiffs taking issue with NAR’s MLS policy, though the trade organization is not named in the long list of defendants—a crucial difference. The lawsuit aimed at the Massachusetts-based MLS and a laundry list of prominent franchisors for implementing the policy.

Despite the similarities in the allegations—although the case is confined to the MLS PIN’s regional footprint—a deal was reached by MLS PIN, where the New England-based MLS would pay $3 million and alter its business practices, which included making the offering of a buyer commission optional rather than required.

While the judge ultimately approved the proposed settlement, the aforementioned DOJ intervention put that deal on ice, and dampened hopes that a minor change in policy would satisfy regulators. That leaves open the possibility that even broad settlements across all the class-action lawsuits won’t be the end of this period of intense scrutiny on real estate.

Cofano believes that the DOJ will indeed keep pushing, as it has filed notices or intervened in many of NAR’s antitrust legal battles in the past.

In this scenario, the DOJ may only be satisfied once the agent commissions are entirely decoupled.

“The government wants a system where there truly is going to be policies in place that will force a negotiation between buyers and buyers’ agents regarding commissions,” Cofano says. “Purely moving the number from $1 to $0 will not result in that.”